If there is one New Year’s resolution I will make tomorrow, it will be TO TRAVEL MORE, both in the United States and beyond. I have the time, and most certainly have the inclination. The wherewithal, however, seems to come in fits and starts so I will just have to grab it when I can. Life is too short to sit still and watch opportunity pass me by.

Looking back over the years I realize I have traveled a good bit in my life, primarily all over the US and in the Canadian Rockies. I visited Jamaica for a week 25 or so years ago, the only time (except for three visits to Hawaii) I have been off the North American continent . I have never been to Central or South America, or Europe, or Asia. Or Antarctica. I want to see all the geology I possibly can in what is left of my lifetime!

I played it safe for several decades, staying too long in a career that sucked the life out of me and that I eventually came to despise. Regretfully I did not travel as much as I should have back then. My recently launched career as park ranger for the National Park Service is a life-long goal finally realized. I get to travel and work in some of the most spectacular geological landscapes on the planet. Still, the seasonal status is a double-edged sword. I get to travel during the winter and work for five months in the summer at places like Katmai NP in southwest Alaska, but I have no insurance or retirement. Of course, there could be worse things than getting a permanent job at a national park.

Have a Happy and Peace-filled New Year!!!

|

| Baked Mountain hut, Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, Katmai NP Sept. 2010 |

Although last week’s storm is now last week’s history, the effect of all that rain and snow melt on Zion National Park’s landscape continues to amaze me. And so, in light of this amazement, I would like to share with you a few final photos of my favorite waterfall. It normally does not exist without a fairly intense storm such as we experienced bringing with it a massive amount of precipitation. This waterfall is usually not here!

|

| My ephemeral falls |

This ephemeral falls is seen along the Observation Point trail in Zion Canyon. The elevation of the trail head is around 4360 ft above sea level…

|

| Observation Point trailhead is at parking lot |

|

| My Christmas Day Tennessee visitors |

|

| Observation Point trail |

…while a point where the trail crosses the run-off is around 5200 ft above sea level.

The waterfall actually drains Echo Canyon and smaller canyons feeding into it from the east side of the park. Without all this rain, though, this (creek? stream? run-off? pour-off? It has no name on my 1987 1:32000 scale Zion NP map) is generally sandy and dry with the occasional pothole full of remnant water and tadpoles. What is not visible (besides me!) in this last picture is the submerged trail as it curves into a narrows to the right.

The waterfall actually drains Echo Canyon and smaller canyons feeding into it from the east side of the park. Without all this rain, though, this (creek? stream? run-off? pour-off? It has no name on my 1987 1:32000 scale Zion NP map) is generally sandy and dry with the occasional pothole full of remnant water and tadpoles. What is not visible (besides me!) in this last picture is the submerged trail as it curves into a narrows to the right.

So what is the height of the falls itself?

We gained about 940 feet elevation in a mile and a half of trail.

If the bottom of the falls is estimated (by me) to be 100 feet above the trailhead, and if the top of the falls is estimated (by me) to be 200 feet below where I am standing as the trail crosses the water (no gps reading here, just my crack eye-balling skills), then the falls should be around 600 feet high.

|

| Can you see the people? |

If there occurs a heavy downpour or a sustained rain in southern Utah, you can be pretty sure that at least some of the hillsides in Zion National Park will end up downstream PDQ.

When the skies finally cleared following a week of steady rain, I went over to the park to have a look at a well-known historic (and recurring) landslide in the main canyon along the Virgin River. I could have just driven to the slide and parked nearly, but what would have been the fun in that? I was, after all, in Zion on Christmas Eve day.

Here is an excerpt from a utahgeology road log for this section of Zion Canyon —

Landslide area makes the narrow V-shaped inner gorge and the debris-littered slopes above. Kayenta beds apparently have slumped to restrict the Virgin River. Kayenta Sandstone blocks are strewn over the more shaly active lower part of the formation. The slump or landslide area appears to have formed a dam across the Virgin River in the past …

For my walk I started at the visitor center and walked up-canyon along the paved Paruus trail for its 1.8 mile length to Canyon Junction where highway 9 crosses the Virgin River in the park.

|

| Paruus Trail |

From the junction it is another half a mile or so to the slide area. This scenic drive follows the course of the Virgin River which is on the left side of the road as you travel up the main canyon.

|

| Zion Canyon scenic drive above Canyon Junction |

|

| Virgin River |

|

||||

| Nearing landslide; scenic drive on right |

In 1996 heavy rains caused a landslide which closed the scenic drive for a week. People at Zion Canyon Lodge were stranded for three days until crews could clear the road. The road section had to be re-built. It wasn’t so bad this time, though. Last week the park was closed for just one day; also, the Lodge and Watchman campground were evacuated. Everything was re-opened the next day.

Only one lane of travel is open on the scenic drive now, but I am not sure why. It didn’t look like the river had washed up onto the road. Perhaps there is some undercutting of the road bed?

|

| Springdale Sandstone is on left of image |

I did not hang upside-down on the retaining wall by my ankles to see what sort of damage had been caused underneath the road near the recent slide.

In the next several images the Virgin River can be seen as it cuts through the recent slide debris.

|

|

|

| Blocks of slumped Kayenta sandstone? Or in-situ Springdale Sandstone? |

Next, I followed this ledgy sandstone out (middle of image); it’s got to be the resistant Springdale Sandstone below the siltstones and sandstones of the slumping Kayenta Formation.

|

| Springdale Sandstone beneath Kayenta slide material |

|

| Top of landslide |

As you stand here and look down the road, the “beehive” of Navajo Sandstone should actually be behind you and to the left. My landslide-photo stitching technique leaves a bit to be desired! The ground-saturating weather system with its thick, gray cloud cover that has stretched across southern Utah for the past week is finally breaking up. Patchy blueness peeking between the unraveling edges of thinning clouds gives hope that the worst of this storm is past. For the first time in seven days, it isn’t raining. I’ll be delighted when the sunshine returns.

The ground-saturating weather system with its thick, gray cloud cover that has stretched across southern Utah for the past week is finally breaking up. Patchy blueness peeking between the unraveling edges of thinning clouds gives hope that the worst of this storm is past. For the first time in seven days, it isn’t raining. I’ll be delighted when the sunshine returns.

It often surprises visitors to the desert southwest that the dramatic scenery which leaves them (and me, for that matter) breathless is often primarily the result of the action of water. Certainly, wind is involved — if strong enough it lifts into the air those particles of sand or clay light enough to be winnowed by the wind; it sweeps along those particles whose mass is small enough to be supported by some particular draft of air.

But it is the water, really — HO in its various frozen, liquid, and gaseous states. We search for it on the Earth, Moon and Mars. Lack of it has caused empires to crumble and civilizations to vanish without a trace. Wars are won and lost over its accessibility. It is our sustenance. Without it, life as we live it would be unattainable. Its powers of weathering and erosion relentlessly alter our landscape, drop by drop, grain by grain.

As I stood along the banks of the Virgin and Santa Clara Rivers yesterday these thoughts crossed my mind. I watched as the turbulent water carried its murky load of silt and logs rapidly downstream. Some of the upended detritus of river life had beached itself on the muddy bank as the peak flow slowed; other flotsam and jetsam had wedged itself upriver against bridge pilings and gravel bars. I thought to myself “So this is how it all happens.” Unremittingly, storm or no storm, the Virgin River and its tributaries eat into the western edge of a small portion of the Colorado Plateau in a classic example of headward erosion: the erosion occurs in the direction from which the river originates. The grandeur that is Zion Canyon was being sculpted grain by grain even as I stood there. Geologic time was passing right before my eyes.

Here in southern Utah we have had an unusually large amount of rain over the past 5 days along with flooding over the past 3 days due to the presence of the Pineapple Express weather system (see previous post for brief details).

The interesting thing about all this water showing up essentially all at once is the amount flowing in the two main rivers near St. George: the Virgin and the Santa Clara. The usually tiny Santa Clara River flows into the bigger Virgin River in the Bloomington area of St. George city. A good portion of our total average annual rainfall (8-12 inches) will have fallen by the time this system passes off to the east.

I wasn’t able to get ever to Zion today to get any photos – hopefully tomorrow. The North Fork of the Virgin River flows through the main Zion Canyon.The typical flow of the North Fork near Springdale (just outside Zion NP) is≈150 cubic feet per second (cfs). On Tuesday 12/21 @ 10:00 AM, the North Fork peaked at 5340 cfsAt 6:00 PM on Wed. 12/22 the peak flow was expected to be ≈4000 cfs

Downstream (from here involving the flow of both the North and East Forks) ≈ 12 miles or so, at the town of Virgin, peak flow on Tues. 12/21 was 8500 cfs

Downstream ≈ 8 miles further at Hurricane, at 10:00 AM Wed. 12/22 the Virgin River peaked @ 5391 cfs. It is forecast to peak at midnight 12/23 Thursday morning at ≈9000 cfsThe typical flow at Hurricane, due (I’m guessing here) to irrigation withdrawal, is ≈70 cfs.YIKES!!!!!

|

| Santa Clara River flow is usually 6 cfs |

|

| Santa Clara River takes out the bike trail but leaves the bridge |

There is also the Santa Clara River (just barely a creek most of the year, or a slightly wide stream…):The typical flow of the Santa Clara River is ≈6 cfs (See? I told you!).Last night the flow was ≈2300 cfs. At 10:00 PM Wed. 12/22 it is predicted to be ≈ 2500 cfs

|

| Virgin River below the confluence – bike trail is washed out |

I mentioned earlier that the usually tiny Santa Clara River flows into the bigger Virgin River in the Bloomington area of St. George city. Tuesday night 12/21 the peak flow below the confluence was 15,822 cfsThe peak is predicted to be ≈ 13,000 cfs at 1:00 AM Thursday 12/23.

As I drove around town today and stopped to watch the river, I was overcome by the power of the water. And so it really comes as no surprise that, over a few million years, the Virgin River is capable of carving Zion Canyon.

Flood warnings continue to beposted through 3:00 PM Thursday afternoon 12/23.

Stats courtesy of weather.gov.

|

|

| Virgin River near Bloomington |

|

|

| I won’t be bicycling here anytime soon |

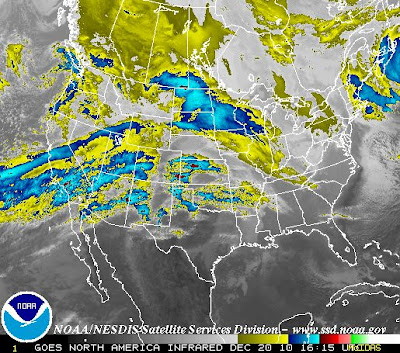

I just had to post these recent satellite weather images, courtesy of www.noaa.gov:  This massive system is known as the Pineapple Express and has its origins in the Hawaiian tropics (clever, huh?). It is full of warm, tropical moisture, can bring in a lot of rain on the west coast, and drop even more in the mountains – since the system is warm it raises the snow levels in the mountains, increasing run-off and melting snow at lower elevations and so adding more water to an already over-saturated situation. The result? Flooding and landslides. Although California usually gets most of the press, Utah is certainly not immune to similar effects – here is the most recent flash flood watch for the southwest part of the state including Zion National Park and the Virgin River:

This massive system is known as the Pineapple Express and has its origins in the Hawaiian tropics (clever, huh?). It is full of warm, tropical moisture, can bring in a lot of rain on the west coast, and drop even more in the mountains – since the system is warm it raises the snow levels in the mountains, increasing run-off and melting snow at lower elevations and so adding more water to an already over-saturated situation. The result? Flooding and landslides. Although California usually gets most of the press, Utah is certainly not immune to similar effects – here is the most recent flash flood watch for the southwest part of the state including Zion National Park and the Virgin River:

Flash Flood Watch Remains In Effect Through Late Wednesday Night The Flash Flood Watch Continues For *A Portion Of Southern Utah Including The Following Areas South Central Utah And Utahs Dixie And Zion National Park. *Through Late Wednesday Night *Deep Moisture Will Continue To Spread Across Southwest Utah Through The First Half Of The Upcoming Week Resulting In An Extended Period Of Moderate To Heavy Rainfall Below 8000 feet. Rainfall Totals Of 3 To 5 Inches Are Expected Across The Lower Elevations Through Wednesday With 5 To 10 Inches Possible In The Mountains Below 8000 feet. *This Moderate To Heavy Rainfall May Lead To Flooding Along Small Streams Slot Canyons And Normally Dry Washes. Significant Rises Are Occurring On The Virgin And Santa Clara Rivers With Bankfull Or Flood Conditions Possible. Precautionary/Preparedness Actions A Flash Flood Watch Means That Conditions May Develop That Lead To Flash Flooding. Flash Flooding Is A Very Dangerous Situation. You Should Monitor Later Forecasts And Be Prepared To Take Action Should Flash Flood Warnings Be Issued.

So although it doesn’t appear that we will have a white Christmas, we can surely expect a soggy one.

Have a safe holiday week, especially if you are traveling!

From late 2005 through mid-2008 I had a lot of fun writing a monthly column for a local southern Utah lifestyles magazine. Each topic could be pretty much anything I chose to write about, but the themes were consistent: hiking and geology. Since this was a popular magazine and not a technical journal I tried to keep the geology as basic as I could without “dumbing it down.” I also didn’t want to write trail guides but just wrote about my experiences in the hope that readers would be able to carve their own personal experience without being directed to hike 1/2 mile and then watch for a cairn. Recently I started sifting through some of those articles and the photos I had taken during the years I wrote the column. It was a thrill at the time to receive so many positive comments from friends and acquaintances; when I finally stopped writing due to my busy school schedule, people often mentioned to me how much they missed my columns. I must have been doing something right.I am dusting off the cobwebs that have accumulated on these articles from my very first paid job as a writer and will post one every week or so for the next few months.

Backpacking in the Uinta Mountains had been on my bucket list ever since I moved to Utah in 1990, so that’s the reason I chose it as the first article to be reborn as a blog post. It took me a few years to get there but I finally made it in the summer of 2007. I hope it isn’t my last visit.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Henry’s Fork drainage and Gunsight Pass |

Whenever anyone mentions the High Uintas Wilderness, an image forms in my mind of ancient mountains weathered by the elements of time. I have wanted to hike these mountains for years but the opportunity never presented itself until this summer when a geologist friend suggested backpacking to Dollar Lake and dayhiking to 13,528 ft Kings Peak, the highest point in Utah. We would go the week of August 20th and would need to prepare, said Ben, “for any kind of weather including snow, sleet, hail, and clouds of low-flying mosquitoes.” It seems backpacking is becoming a lost art among us aging baby boomers. I started backpacking in the early 1970’s while attending the University of TN in Knoxville in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. I plan to keep at it until I am no longer able to crawl out of my tent on my hands and knees and stand up.

I would hike in on Monday, a day earlier than Ben and Jeff and Jeff, to give myself as much time as possible in mountains I may not see again for a while. We would regroup at Dollar Lake Tuesday afternoon, hike to King’s Peak Wednesday, and hike down Thursday. From the outset I didn’t think I would do the peak, but that was fine. To me, the journey is the destination, wherever that might be. “OK, then,” said Ben. “I’ll see you on the mountain.”

According to current geologic thought, the Uintas are a result of a northerly-trending rift that occurred sometime around 1 billion years ago on the western edge of the ancient North American proto-continent of Rodinia. A 2nd rift formed perpendicular to this by around 800 million years ago, sediments from adjacent highlands had deposited into this 2nd rift basin. Uplift of these sediments 50-70 million years ago during the Laramide Orogeny (mountain-building) formed the Uinta Mountains.

The previous week our weather had been unsettled and stormy but the forecast called for clearing skies. If storms threatened I would just wait it out until my friends arrived the next day. These mountains create their own weather – clear skies at the trailhead were no guarantee of the same at higher elevations.

I gave my brother Larry my itinerary – which drainage I’d be in, when my friends would arrive, which day I expected to hike out. I stayed in Roosevelt 2 days then headed for highway 191, an extremely scenic route north from Vernal. This spectacular drive across the eastern flank of the Uintas has road signs describing the geologic formations. When I saw signs for the Precambrian (older than 540 million years) Uinta Mountain Group I had to toss some rocks into the back of my car. Really old rocks just knock my socks off. These are not the oldest in Utah but at nearly 1 billion years old they have a story to tell.

I gave my brother Larry my itinerary – which drainage I’d be in, when my friends would arrive, which day I expected to hike out. I stayed in Roosevelt 2 days then headed for highway 191, an extremely scenic route north from Vernal. This spectacular drive across the eastern flank of the Uintas has road signs describing the geologic formations. When I saw signs for the Precambrian (older than 540 million years) Uinta Mountain Group I had to toss some rocks into the back of my car. Really old rocks just knock my socks off. These are not the oldest in Utah but at nearly 1 billion years old they have a story to tell.

As I pulled into Henry’s Fork trailhead on the north slope of the Uintas around 9am, a car pulled in behind me and 2 people about my age got out. They introduced themselves as Tim and Patricia from Rochester NY and were setting out to camp at Dollar Lake with the intent of hiking to Kings Peak on Tuesday. We talked for a few minutes and then fell in to hiking together the entire 7 miles to the lake. Surely they thought “Oh this poor woman with her heavy pack – we can’t let her hike alone!” We laughed and talked like we had known each other for years, and soon morning passed into afternoon. I had planned on 7 hours hiking. We took lots of breaks, savoring our moments in time as we gained elevation to nearly 10,800 ft. So as we hiked further into the High Uintas Wilderness we related our personal stories to each other, and the mountains listened, and whispered their own story.

As I pulled into Henry’s Fork trailhead on the north slope of the Uintas around 9am, a car pulled in behind me and 2 people about my age got out. They introduced themselves as Tim and Patricia from Rochester NY and were setting out to camp at Dollar Lake with the intent of hiking to Kings Peak on Tuesday. We talked for a few minutes and then fell in to hiking together the entire 7 miles to the lake. Surely they thought “Oh this poor woman with her heavy pack – we can’t let her hike alone!” We laughed and talked like we had known each other for years, and soon morning passed into afternoon. I had planned on 7 hours hiking. We took lots of breaks, savoring our moments in time as we gained elevation to nearly 10,800 ft. So as we hiked further into the High Uintas Wilderness we related our personal stories to each other, and the mountains listened, and whispered their own story.

|

| Dollar Lake |

The first few miles passed quickly but then climbing became steeper and walking slower. I considered jettisoning my binoculars along the way (Why in the world did I bring those?). By the time I crawled in to my tent that night I was totally hammered. My pack had weighed a ton. I was coughing; my feet, ankles, and knees ached. I was desperately searching for those pesky oxygen molecules I knew had to be there somewhere at that elevation. But I made it! I had wanted to hike the Uintas for a long time, and finally made it.

|

| Sheepherder with border collies |

Tuesday, Tim and Patricia left at dawn for King’s Peak. I had a leisurely morning sitting on a log in the quiet woods, eating pop tarts and drinking chocolate coffee. Mid-morning I set out for Gunsight Pass at 12,000 ft on the route to the peak. Henry’s Fork drainage is an expansive glacier-carved U-shaped valley with steep cliffs on both sides. Nearing the pass in the headwall of the drainage the trail skirts the eastern cliff. I wondered if I would be scrambling up a steep scree slope, but at the last minute the trail switchbacked up to the right. It was easy going, not too steep, and pure joy without a heavy pack. At the next switchback I found a flat rock to set myself upon and watched 3 border collies and a sheepherder on horseback make their way up the trail. It was cool and breezy and sunny and warm. Gunsight Pass was at eye level from my rest spot, the trail contouring gently along the mountainside. I continued on, studying some exposed bedrock at the pass. Most of the valley floor consists of rock debris left from the retreat of the last glaciers around 10,000 years ago, so finding this bedrock was exciting.

Slowly, because I wanted to imprint the view in my memory, I made my way back to camp. On my tent was a note that Ben and Jeff and Jeff had arrived. I needed to refresh after 2 days on the trail – Dollar Lake was too inviting not to just wade in and plop down to cool off. It was cold but felt wonderful! All that aching and soreness disappeared. Tim and Patricia came back around 7pm with stories of their day. I was glad they were safe. Wednesday morning they said goodbye and headed down the mountain. I’d had an unexpected good fortune in meeting and hiking with them, and hope they have as good a memory of me as I do of them. Ben and Jeff and Jeff were off to Kings Peak early, but since at this point I had no desire to “bag the peak,” I just moved my tent nearer to theirs and again had a leisurely morning.

Slowly, because I wanted to imprint the view in my memory, I made my way back to camp. On my tent was a note that Ben and Jeff and Jeff had arrived. I needed to refresh after 2 days on the trail – Dollar Lake was too inviting not to just wade in and plop down to cool off. It was cold but felt wonderful! All that aching and soreness disappeared. Tim and Patricia came back around 7pm with stories of their day. I was glad they were safe. Wednesday morning they said goodbye and headed down the mountain. I’d had an unexpected good fortune in meeting and hiking with them, and hope they have as good a memory of me as I do of them. Ben and Jeff and Jeff were off to Kings Peak early, but since at this point I had no desire to “bag the peak,” I just moved my tent nearer to theirs and again had a leisurely morning.

It is a sublime experience to doze in a tent in the shade of evergreens and have absolutely nothing else to do, so that’s what I did. Early afternoon I shook myself awake and moseyed up the trail to meet my friends on their way down. These guys are strong hikers and they were exhausted, so I was glad I hadn’t gone. I’d probably still be up there. Alicia and George from SLC arrived to hike to the peak the next day, so that evening we relaxed in the deepening dusk as we passed around the flask. Our weather had been perfect. I had counted 3 mosquitoes.

It is a sublime experience to doze in a tent in the shade of evergreens and have absolutely nothing else to do, so that’s what I did. Early afternoon I shook myself awake and moseyed up the trail to meet my friends on their way down. These guys are strong hikers and they were exhausted, so I was glad I hadn’t gone. I’d probably still be up there. Alicia and George from SLC arrived to hike to the peak the next day, so that evening we relaxed in the deepening dusk as we passed around the flask. Our weather had been perfect. I had counted 3 mosquitoes.

In the morning I hiked out with Ben as we spoke of glacial advances and retreats, billion-year-old quartzites, ancient mountains weathering by the elements of time, and how our fascination with the geology of the Uintas allows us to peer ever so slightly into eternity.

FYI:“High Uinta Trails” by Mel Davis and John Veranth has good trail descriptions. Trails Illustrated Map of the High Uintas Wilderness, Uinta Mountains, Kings Peak, Utah, USA gives a good overview. For more detail refer to USGS topo maps of Kings Peak and adjacent quads.My invaluable reference is “Geologic History of Utah” by Lehi F. Hintze.