The theme of my last post on the Taylor Creek Thrust Zone of Zion National Park continues here with the Kanarra Fold, a landmark that can be seen for miles along interstate 15 in southwestern Utah just outside the boundary of Zion National Park.

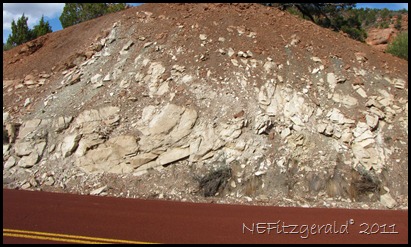

The wrinkles in our geologic rug were also squeezed and uplifted 12 miles southward from Taylor Creek to produce the Kanarra Fold, where Permian limestones plunge earthward on the eastern arm of the fold.

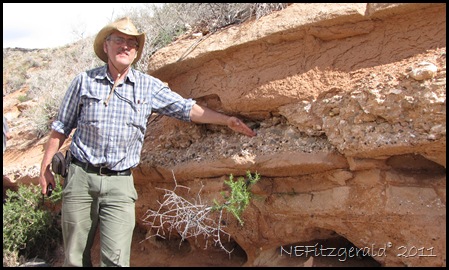

Look closely at the folded rock layers. Is there anything reminiscent of the Taylor Creek Thrust Zone?

How about this?

Much as the Kayenta Springdale Sandstone was shoved over itself in the Taylor Creek Thrust Zone, so were these older Permian Kaibab limestones shoved over themselves.

Again, this spectacular faulting is seen on the east flank of the fold.

Perhaps as early as 150 million years ago during the Jurassic period of geologic time, western North America began to experience “pushing” from the west as the denser Pacific plate began a relentless slide beneath a more buoyant North American plate. Like wrinkles in a rug pushed up on a hardwood floor, the rocks of the Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park were squeezed, gently folded, and broadly uplifted over a period of nearly 100 million years.

|

| Folding and faulting near Taylor Creek, Zion NP |

When compressional stress is applied gradually enough, rocks fold in on themselves and can yield like silly putty while not fracturing. But when compressional forces are applied swiftly enough, deformation occurs with the development of brittle thrust faults in which rock layers fracture and are thrust over themselves.

I was able to take a look at some of this structural geology the other day as I drove south from Cedar City UT. In particular, I wanted to see once again where the Moenave Formation was shoved over itself as part of the Taylor Creek Thrust Zone. The Springdale Sandstone member of the Moenave is the prominent cliff-forming rock layer, while the Dinosaur Canyon member forms the bleached white layer beneath it.

|

| Springdale Sandstone thrust over itself |

During tectonic compression, the Kannara Fold was formed as a major crustal wrinkle in what would one day become the northwest corner of Zion National Park in southwestern Utah. As the wrinkle became more intensely folded over time, brittle fractures developed on the eastern flank of the fold, allowing the rock to be thrust over on itself.

The rocks I came to look at are on the east flank of the fold. The upper part of the thrusted block has moved the Springdale Sandstone from the east toward the west over itself.

|

| Drag fold in Dinosaur Canyon member |

It was suggested to me that while I was in Kolob Canyons I should also take a look at the Albino Dino, the bleached white Dinosaur Canyon member found below the Springdale Sandstone. “You can see a drag fold in the road cut!”

I’ll be the first to admit I had to stand there for a while, pondering a sense of movement in the rocks. I considered the thrust faulting in the Springdale Sandstone I had been looking at, and its location just above the Dinosaur Canyon member, and realized these rocks were related to that thrusting.

I noticed the fault area between the upper and lower arms of the fold. Here was the drag fold, a minor fold in the rocks due to shear resulting from slippage on a fault. The (faint!) red arrow in the image below indicates this area of slippage.

|

| Drag fold along a small reverse fault |

The drag folding along a reverse fault (which is what I believe we are looking at here) can be better visualized if the diagram is flipped so that the fault line dips in the other direction. The rocks that are the recipients of the dragging would be the upward-curving rocks to the left.

|

| Image courtesy of nasa.gov |

|

| Thrust faulting and drag fold, Kolob Canyons, Zion NP |

Reference:

Hamilton, W.L., 1984, The Sculpturing of Zion with road guide to the geology of Zion National Park, Zion Natural History Association.

Standing in my brother’s southern Utah yard this sunny springtime afternoon, I got to looking around at his desert landscaping and started thinking (always a scary endeavor). If I had been in this exact location around 260 million years ago, I would have been looking at the great-great-great-great-great ancestors of these landscaping rocks. Most likely I would have enjoyed using a snorkel, mask, and flippers at the time.

The rocks are Permian limestones, laid down in warm, shallow tropical waters when Utah was about ten degrees north of the equator and the Kaibab Sea covered much of the western edge of ancient Pangaea. Over tens of millions of years, the future Utah would either have been submerged under a mere few meters of water or been barely above sea level.

I honestly do not know for sure if these blocks were quarried from the sedimentary rocks of the older Toroweap Formation or the overlying (and younger) Kaibab Formation, but I expect that the quarries are local. These two formations are quite prevalent in southwestern Utah near St. George, forming the massive Hurricane Cliffs along interstate 15 from near Cedar City south to Anderson Junction. Large tracts of Washington County countryside are Permian limestones, and the rocks can be followed further south into the extreme northwest corner of Arizona, again forming massive cliffs in the northern reaches of the Virgin River Gorge.

|

| Chert nodules in Kaibab limestone |

Chert is an interesting rock, and to me these chert nodules are spectacular. Chert is a very fine-grained sedimentary rock with a tough, splintery, conchoidal fracture and consists predominantly of interlocking crystals of quartz. It occurs mainly as nodules or concretions in limestones (CaCO) and dolomites (CaMg(CO) and less commonly as layered deposits or “bedded” chert.

|

| Chert nodules in limestone |

|

| Silica replacing limestone in nodule |

But how does the quartz chert get into the limestone and dolomite, anyway? As I understand things, at some point in the distant past, groundwater containing dissolved silica (SiO) moved through fractures in the limestone. It might have only taken one miniscule grain of silica to precipitate out of the water to form the “seed” or core of the nodule. Over time the nodule grew from that seed of silica. Another explanation is that the silica replaced calcium carbonate or CaCO as once again silica-rich fluids moved through the fractured rocks of the ancient Kaibab Sea.

Calcite is the common rock-forming mineral of calcium carbonate (or limestone). A drop or two from a small bottle of dilute hydrochloric acid comes in handy for checking the “fizz” of calcite and also limestone in general.

|

| Calcite crystals |

These limestones happen to be fairly fossil-rich, , too. Bryozoans, brachiopods, crinoids, corals, and sea urchins are commonly found. Bryozoans were (and still are) colonial animals which secreted a hard, limy skeleton. They are not the same as corals and are not plants.

|

| Bryozoan |

These fossils in the chert nodule look like they might be bryozoans.

Brachiopods (below the penny) have been around for 500 million years. Many of the species became extinct at the end of the Permian Period (around 350( oops!) 250 million years ago) but others still thrive today. They are solitary marine invertebrates and have distinctive bilaterally symmetrical shells.

|

| Brachiopod (below penny) |

A few other items also caught my eye as I wandered about in this southern Utah yard… I could not identify this lizard, but wonder if that protrusion is its ear (between its eye and foreleg). Plus – check out those feet!

When I mentioned recently that I would be working at Yellowstone this summer, an old (not ancient!) ranger friend at Arches wrote that he “predicts many supervolcano posts” on this blog. I too have a prediction of my own – that I will have a wonderful time discovering and writing about the geology and wildlife found in our first national park. It’s been over 30 years since I’ve been to Yellowstone and I am beyond excited to be going.

When I mentioned recently that I would be working at Yellowstone this summer, an old (not ancient!) ranger friend at Arches wrote that he “predicts many supervolcano posts” on this blog. I too have a prediction of my own – that I will have a wonderful time discovering and writing about the geology and wildlife found in our first national park. It’s been over 30 years since I’ve been to Yellowstone and I am beyond excited to be going.

Work starts May 15, and I will be busy the next few weeks packing and getting things ready for life in government housing. For now, I offer a photo journal of some of the national parks I have had the pleasure to visit and/or work at over the years. Click on the image for its description. Enjoy!

MONTANA…

MONTANA…

If I could have given away prizes for the first correct answer and best clue to my recent contest, here is what I might have offered.

For the first person to correctly guess the name of the national park, wouldn’t you have loved to own this stunning early 1960’s gem? My own personal dream car is the 1955 or 1956 convertible model, but this one would do in a pinch.

For the participant who offered the best clue, this next vehicle of unknown make, model, or vintage would have been a lovely addition to any front yard decor.

You can find these jewels of automotive history at Cold Springs and nearby historic Middlegate Station located in central Nevada on Highway 50, The Loneliest Road in America.

|

| Cold Springs, Nevada |

Was it the clue “ginormous shallow magma chamber” that ultimately was the dead giveaway for the successful entrants who figured out here ill ina ork “Geysers” must have been a front-runner, too. Now the entries have been tallied, and the winners are – Everyone!

Glistening travertine terraces, bubbling hot springs, boiling mud pots, and hundreds of steaming geysers combine to make Yellowstone National Park the most extraordinary and complex thermal area on earth. Its giant calderas are evidence of at least three explosive volcanic eruptions over the past two million years. Over a mile above sea level, Yellowstone Plateau has been built up by layers upon layers of volcanic ash, lava, and breccia.

Thanks to everyone who submitted entries. I have no car to give away for first prize, but I do hope that if you are at Yellowstone this summer you will let me know. I would be thrilled to spend time showing you any “special places” that I look forward to discovering while I am there. Or perhaps you might have discovered some on your own that we can explore.

Competition is fierce to guess Where Will Nina Work this summer! For those of you who have not submitted an entry yet, this post offers a few more enticing clues.

Competition is fierce to guess Where Will Nina Work this summer! For those of you who have not submitted an entry yet, this post offers a few more enticing clues.

Today the sky is the limit. You can submit two entries. For that matter enter three times. You can also change any previous guesses.

Here are the final clues of the contest:

6) Geysers

7) Hot springs

8) Ginormous shallow magma chamber

9) First national park in the US (1872)

These clues are so enticing you have no choice but to know the answer.

Winners will be announced on Monday!

The contest to guess here ill ina ork is now moving forward like a herd of turtles! However, coming up with clues that are not dead giveaways is harder than it looks. Consider this insightful comment from one sharp-eyed contest entrant who just happens to know where I am going:

The contest to guess here ill ina ork is now moving forward like a herd of turtles! However, coming up with clues that are not dead giveaways is harder than it looks. Consider this insightful comment from one sharp-eyed contest entrant who just happens to know where I am going:

“I can think of lots of clues, but the ones I come up with are dead give-aways. Hmmm…. this is harder than it looks.”

She clearly wants the prize for the best clue by someone who already knows where I am going.

Be that as it may, here are the next clues to help you guess WWNW!

3)This national park was designated a World Heritage Site in 1978

4)Native Americans hunted and fished in the area for thousands of years. Yes I know this clue applies to pretty much everywhere on the North American continent, but I thought I’d include anyway.

5)Many features of the landscape are associated with volcanic events that took place in relatively recent geologic time.

Get the first two clues and comments at yesterday’s post

Many of you may be aware that in recent years I have worked as a seasonal park ranger for the National Park Service. Moreover, I am anticipating doing so again this summer, the intransigence of our United States Congress notwithstanding.

Many of you may be aware that in recent years I have worked as a seasonal park ranger for the National Park Service. Moreover, I am anticipating doing so again this summer, the intransigence of our United States Congress notwithstanding.

Last year I worked at Katmai National Park in southwest Alaska, hiking in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and directing human traffic to avoid brown bears that were more intent on devouring salmon than people.

In 2009, I spent my first season as a park ranger at Cedar Breaks National Monument in southern Utah among 1000-year-old bristlecone pines and 50-million-year-old lakebed sediments.

This week I accepted a 2011 NPS job at a different park, and am beyond excited to be spending the summer there. But, just where is there? here ill ina ork?

Enter the contest to guess where I will be working! I will post frequent clues on this blog. To make it easy for you, clues will be taken directly from the park’s website. OK, well, most of them will. Some clues will pop directly out of my head.

Submit your contest entry as a comment. You can win!!!

If you already know where I will be working (because I already told you – and I know who you are), you can still participate! Just suggest some clues in the comments section of the posts.

Are you ready to put on your detective hats! Here are the first clues:

1)This park is home to a large variety of wildlife. Look for bears, wolves, elk, and buffalo.

2) Visitors often say they come here to experience the “idea” of the national parks.

You can find information about all the national parks here

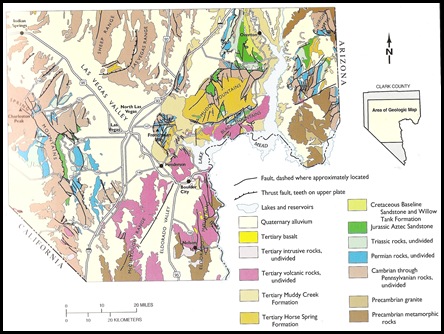

A moonless, star-splattered night sky rimmed by massive cliffs of the Virgin River Gorge and a campfire that could probably be seen from the international space station were the last things I remembered as I drifted off to sleep at Cedar Pockets campground, the growling of eighteen-wheelers grinding their gears on nearby Interstate 15 a constant background drone.

The stars had disappeared with the morning light but the roar of traffic remained. We drank our cowboy coffee, ate our instant oatmeal, packed up our gear, and wedged ourselves cozily into our three rented vehicles for the second day of the Southern Utah University Geology Symposium field trip. We left the trailer at the campground where we would retrieve it on our way home.

|

| Virgin River Gorge, AZ |

|

| Cedar Pockets campground |

|

| Aztec Sandstone at Whitney Pocket |

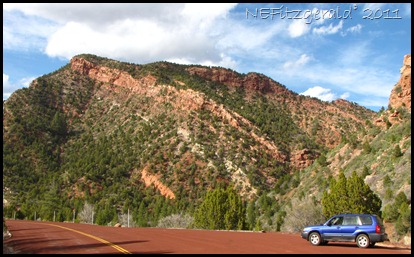

We drove south beyond Mesquite, Nevada to Whitney Pocket, an area near Lake Mead rich with petroglyphs etched in windblown desert sand deposits of the ≈190-180 million-year-old Early Jurassic Aztec Sandstone (one and the same as the Navajo Sandstone of Zion National Park).

The geology of the southern Nevada/Lake Mead area is complicated by exposed Mesozoic thrust faults, exhumed tilted fault blocks of Precambrian crystalline basement rocks, extensive Tertiary volcanism, strike-slip faults of the right-lateral Las Vegas Valley shear zone, and the left-lateral Lake Mead fault system.

|

| Image courtesy of Geologic Tours in the Las Vegas Area |

Sedimentary rocks of the Horse Spring Formation were a result of crustal extension in southern Nevada between ≈17-10 million years ago. The rocks most likely were deposited in large basins that contained periodic lakes during a time of less arid desert conditions. There is much tectonic history with these rocks, notably regarding movement of Frenchman’s Mountain, presently near Las Vegas, 50 miles along a fault-guided path.

However, what we were looking for on this day was evidence to support a theory that the Colorado River had flowed north along a course into Canada ≈20 million years ago. The basal Horse Spring Formation would be the conglomerates of the ancient Colorado River channel (click here for James Sears’ abstract from symposium).

We searched for gravels at a lunch spot, but it turned out we were on the wrong side of the ridge. Note spare tire on the vehicle on the right.

After lunch we checked the map and were soon bouncing back down the graded road. A turn here and a turn there, and we eventually found what we were looking for – the basal member of the Horse Spring Formation.

|

| Outcrops of Horse Spring Formation |

Interestingly, these imbricated gravels, arranged like shingles on a roof, show that the direction of river flow was to the left. It totally blows me away when I see these structures in the field – they become so much more real and comprehensible and are not just pictures in a textbook.

|

| imbricated gravel showing flow of water to the left |

|

| travertine |

We chatted about why these various–sized white travertine clasts were deposited here and where they had come from. Travertine is a sedimentary carbonate rock composed of calcite or aragonite with some impurities. It derives from the evaporation of calcium carbonate–rich spring waters near waterfalls and in rivers (the Colorado River of 20 million years ago, perhaps?) and now commonly occurs in the Great Basin of Nevada.

Daylight burned as we were absorbed in the Horse Spring Formation but ultimately we had to leave. Somewhere along this scenic piece of real estate our second (or was it our third?) flat tire hit us. With such a lovely angular unconformity in the distance, though, it was difficult to stress over anything – except what we would do if we had another flat.

|

| angular unconformity |

We all kept our fingers crossed. The plan had been to go down Elbow Canyon and examine a section of the shear zone encompassing the entire mountain of Precambrian metamorphic rock, but our dire tire situation led us to take a somewhat less rubble–strewn route down and out of the Virgin Mountains.

Our last but not least stop was at an outcrop of sheared metamorphic rock. We found some samples of what looked like an eclogite and tossed them in the vehicle to take back to the thin section lab. We then had our fourth flat tire crossing the alluvium into Mesquite. By now the sun was inching itself down to kiss the horizon.

We were totally tired of tires and entirely out of spares.

|

| Virgin Mountains |

Cell phones whipped out faster than a roadrunner on speed. It took a while to arrive at a consensus of sorts. In the end, though, the consensus took on a life of its own as soon as the first vehicle drove away to somewhere acquire a tire and have it transported back to the spareless remaining vehicles. We did not really have all our rocks in a row but we seemed to be making incremental progress towards home.

Then the vehicle in charge of tire procurement had the fifth flat, 11 miles north of Mesquite. All we could do at that point was call AAA. We sat on the side of Interstate 15 for an hour and a half, in the dark, as traffic whizzed by. We never did see the other two vehicles.

There is much more to the story but I have exhausted myself relating this part of it.

Our vehicle was towed 100 miles and I would not be surprised if the other two had been left abandoned by the side of the road. Someone picked up the trailer at Cedar Pockets campground. I got home at midnight and the Cedar City/SUU contingent got home around 3:30 Sunday morning.

I definitely want to know who is in charge of field trips next year.

|

| Desert marigold |

References:

Tingley, J.V. et al., 2001, Geologic Tours in the Las Vegas Area Expanded Edition, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Special Publication 16

http://geopubs.wr.usgs.gov/open-file/of99-435/ (accessed 4-6-2011)